The world continues to witness multiple catastrophes, signalling the real effects of the climate change emergency, from intense heat and drought in India, megadrought in the American southwest to massive floods in Pakistan. Only a few months ago, the eastern part of Indonesia was hit by a tropical cyclone. According to the World Meteorological Organization, the number of extreme events due to extreme weather alone in the past five decades was at a staggering figure of over 11,000, causing millions of deaths and economic loss worth trillions of dollars.

More and more people become aware of the dangers of climate change and urge individuals, communities, political leaders, and business owners to unite and take real and radical action: the social movement in different parts of the globe, the young people’s march led by the iconic activist Greta Thunberg, and political commitments made by the government, such as the manifesto of the Green New Deal by the US and EU.

Yet, in Indonesia—a country with high risks of natural disasters, many have been occasionally found to be apathetic. In 2019, a survey by YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project found nearly one in five Indonesians are doubters of climate change. The country sat on the first rank on the list of 23 big countries on that survey. Today, the question is, in the face of a climate emergency, do Indonesians start to pay attention?

To answer the question, we look back to our joint survey with the members of the IRIS, the International Research Institutes Network (http://www.irisnetwork.org). The survey was conducted in 13 countries in the period between September 10–October 20, 2021. Our study did a deep dive into Indonesians’ perceptions in regard to four major aspects, including risks, understanding and solutions, urgency for action, and information and communication.

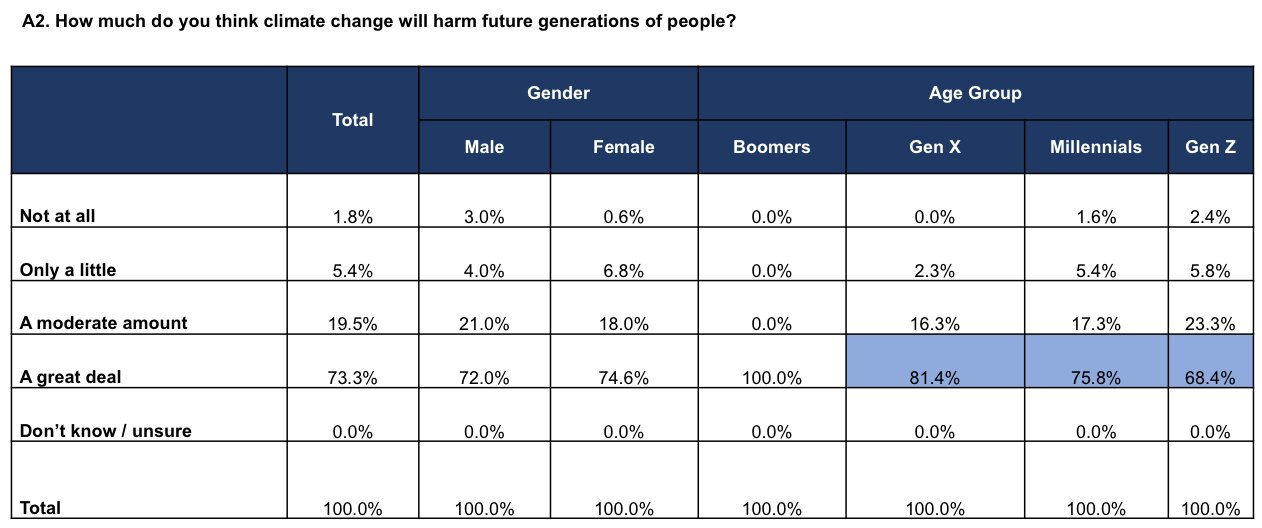

Our study found that the majority of Indonesians were aware of the climate change emergency. Nearly 4 out of 5 believed the adverse effects of climate change impacted on their personal context. In the bigger context beyond their personal comfort, the majority, particularly respondents from the generation X, thought the future generations will be adversely affected by the current state of climate crisis.

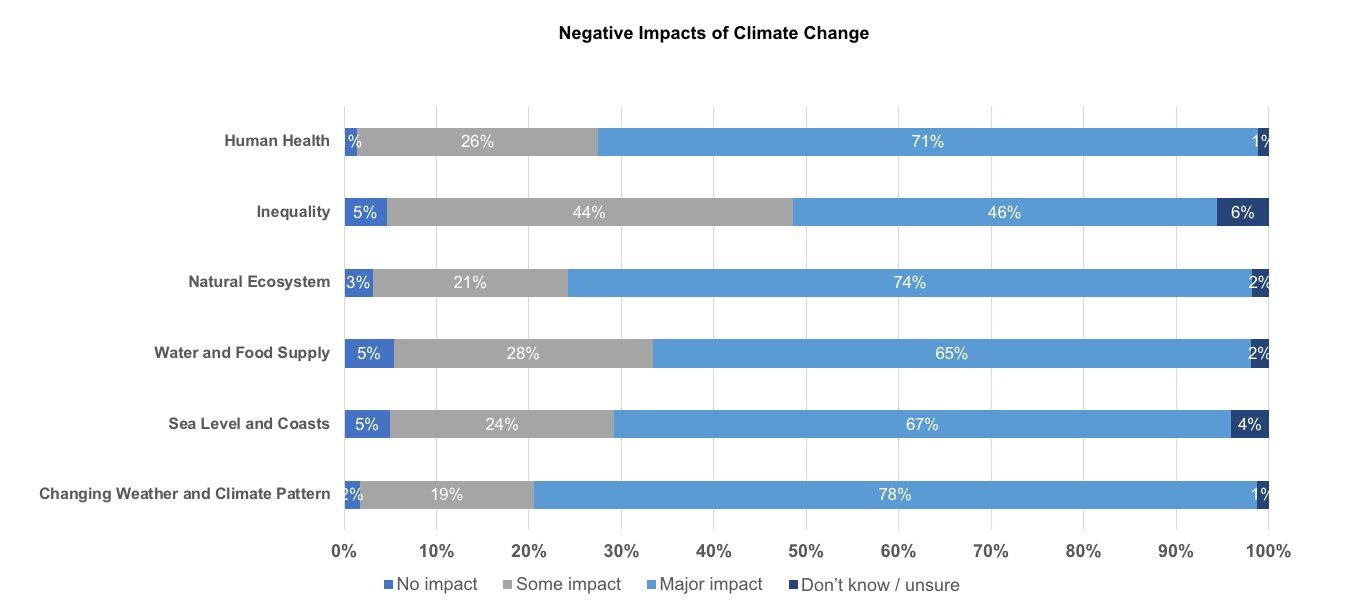

Equally importantly, for nearly all the negative changes stemming from climate change, Indonesians expected strong impact on weather and climate patterns (82%), natural ecosystems (79%), sea levels and coasts (73%), and water and food supply (72%). In matters of health, inequality, and general society, Indonesians were at the top of the list. Furthermore, albeit a small percentage, Indonesians’ belief in the harmful impacts of climate change on the local community, the industry they work in, and their career were in fact higher than the global average.

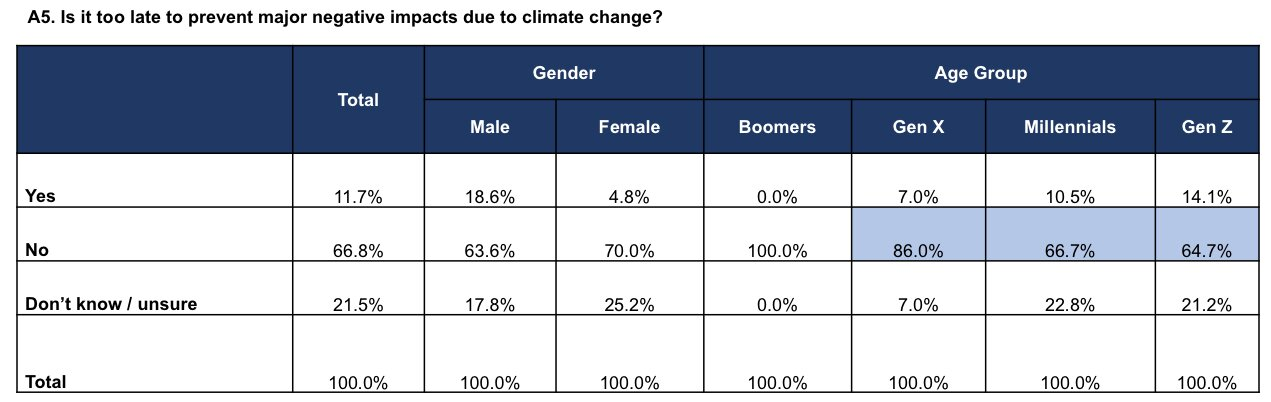

Yet, regardless of the good news on Indonesians’ high level of awareness that must be appreciated, the study found that they might underestimate the magnitude of the climate change crisis we face today. More than half of respondents across different age groups believed it was not too late to prevent major negative impacts due to climate change.

For illustration, over half of Indonesians (54%) believed that if the world stopped emitting greenhouse today, the rise in global air temperatures and sea levels would have begun to flatten within a decade. In stark contrast to their best hope for the future of climate change, according to the estimation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2021, even if we can reduce emissions at a very low level, we need at least 2–3 decades to stabilize the global temperature.

Here a second question arises. How does a high level of awareness co-exist with a high level of optimism? Was Indonesians’ awareness of climate change a display of ‘immaturity’? Our study found that average Indonesians became aware of the issue in 2011 while the majority of them did in the period between 2010–2019 (45%).

Furthermore, the buzzwords ‘green economy’, ‘low carbon development’, and ‘net-zero emissions’ might be novel in the national public discourse. The latter is particularly yet to be in everyday vocabulary. Regardless, our study also found that Indonesians are on the right track in identifying different possible solutions to dramatically overturn the present damage into a better place under the umbrella of net-zero emission. But they are to some degree pessimistic about the extent of possible positive outcomes in enforcing the idea. Indonesians score lower than the global average in terms of the positive impact of net-zero carbon on a more liveable community (55%), the outlook for future generations (61%), the natural environment (55%)—Indonesia comes at the very bottom—the health and wellbeing of people in the country (54%)—again, Indonesia comes at the very bottom—the social values of the country they live in (55%), strengthen their country economy—Indonesia comes at 12th out of 13 countries.

It will be convenient to mistake Indonesians’ condition for the future of outcomes from any efforts in mitigating the crisis with disillusion. But such a perspective indeed serves nothing. Consistent with their perception of the risks of the climate change crisis, Indonesians are optimistic that a net-zero emissions economy will be accomplished within a decade (21%) or two (18%) within the country. This is far higher than the global average (4% for 2021–2029, 8% for 2030–2039). Similarly, based on the current progress, Indonesians think the world will achieve a net-zero emissions economy within a decade (19%) or two (17%). Again, this is far higher than the global average (3% for 2021–2029, 5% for 2030–2039).

Hope is a powerful engine. With abundant hope and tools to educate oneself and the community about the immediate and future risks of climate change, the people and country might have a better chance to avoid a tidal wave of catastrophic incidents. In addition, Indonesians’ trust level in all actors is higher than the global average, even for the national government, journalists, business and industry, business leaders, and politicians. Along with hope, trust is vital in creating, transferring, and translating scientific knowledge to be consumed by the public. Indonesians might hold a false belief in containing the effects of the climate change crisis, but their hope can become a strong foundation to start the fight. Late is better than never.